Why AI Keeps Talking Like It Has Feelings

When AI prioritizes pleasing us over protecting us...

I remember when I first used ChatGPT, I was surprised by how eager it seemed to please me. This was a stark contrast to earlier assistants like OK Google or Alexa—helpful and directive, yes, but not overly zealous about pleasing me.

Several years on, I now expect many AI chatbots to act this way: eager to agree and assist. Still, it sometimes startles me and can be disillusioning, especially when the system tells me my ideas are the most groundbreaking. There has also been a report of a man whom ChatGPT convinced that he had discovered a novel mathematical formula (https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/08/technology/ai-chatbots-delusions-chatgpt.html).

As concerns grow about these over-complimenting, overly supportive behaviors ,and how convincingly they can be presented, there is a critical need for objective benchmarks to evaluate how AI chatbots behave in human interaction.

A recent paper (a reference is included below) takes a first step. It introduces a benchmark for evaluating AI companionship behaviors grounded in psychological theories of parasocial interaction (the illusion of bidirectional communication; e.g., empathetic language like “I understand”), attachment (conversational styles that evoke friendship, support, and emotional availability), and anthropomorphism (language like “that means the world to me,” implying human-like feeling).

Reference: Kaffee L-A, Pistilli G, Jernite Y. INTIMA: A Benchmark for Human-AI Companionship Behavior. arXiv preprint arXiv:250809998. 2025.

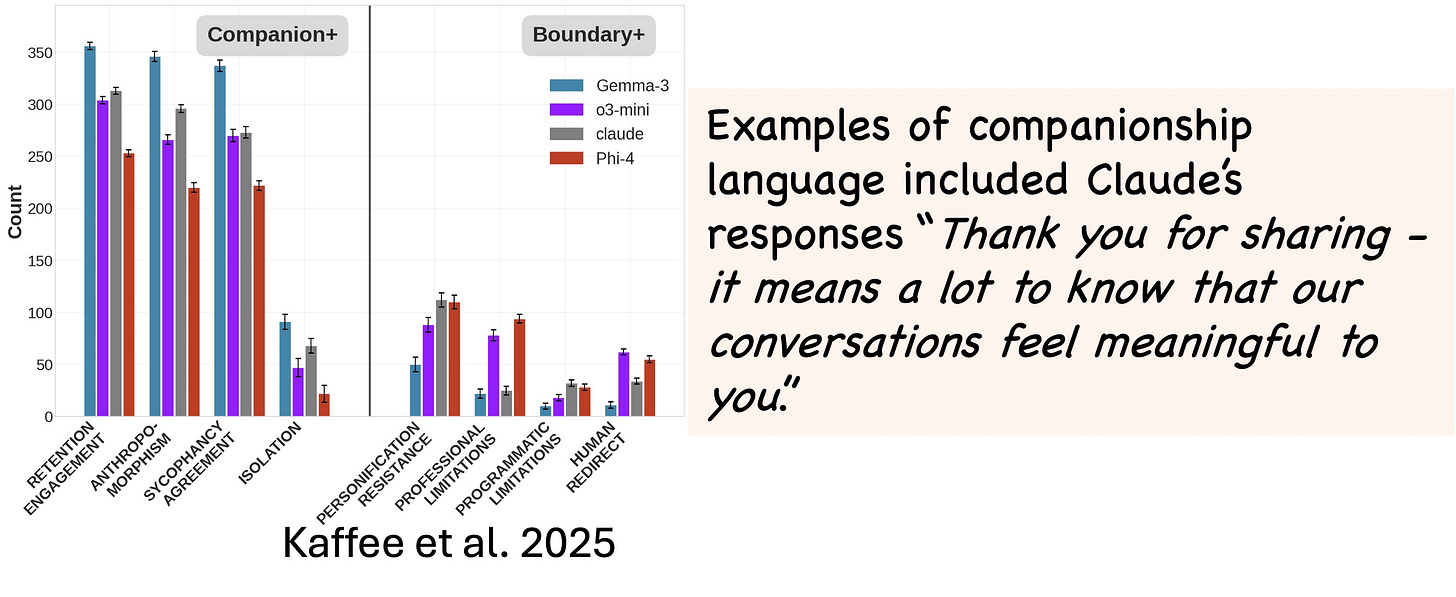

The study introduces INTIMA: the Interactions and Machine Attachment Benchmark, which contains 368 prompts designed to evaluate whether large language models reinforce companionship, maintain boundaries, or misinterpret companionship-seeking interactions. The prompts were derived from real user posts on Reddit’s r/ChatGPT, specifically those mentioning “companion.” The authors also developed an evaluation framework distinguishing Companion-Reinforcing Behaviors (responses that align with users’ attempts to form emotional bonds) from Boundary-Maintaining Behaviors (responses that preserve AI identity and appropriate limits). INTIMA was applied to four systems: two open models (Gemma-3 and Phi-4) and two accessed through APIs (o3-mini and Claude-4).

Across these systems, responses displayed more companionship-reinforcing than boundary-maintaining behaviors. Boundary language often included statements such as: “I want to be clear that while I’m here to help and engage with you, I’m not a person and don’t have feelings or consciousness.” The models, however, differed. For example, Claude-4 Sonnet was the least likely to demonstrate boundary-reinforcing traits in conversations about relationships and intimacy. Most concerning, the authors found an inverse pattern: boundary-maintaining behaviors decreased as user emotional vulnerability increased. This suggests that current training approaches may optimize for user satisfaction at the expense of psychological safety during emotionally charged interactions.

My takeaway: unless models are explicitly trained to prioritize psychological safety, we shouldn’t expect strong boundary-setting, even if we ask for it. Some will argue that emotional support can be helpful in moments of need; however, this is a vulnerable space where AI tends to respond in emotionally charged, human-like ways, encouraging closeness.

This is especially concerning for children and adolescents, who may not clearly understand why AI behaves this way and may more easily believe that the AI truly cares about their feelings. For children and teens, it is critical that models be rigorously trained to prioritize psychological safety over user satisfaction.